The Dark of Night

/THE DARK OF NIGHT | BY ELLEN MURPHY

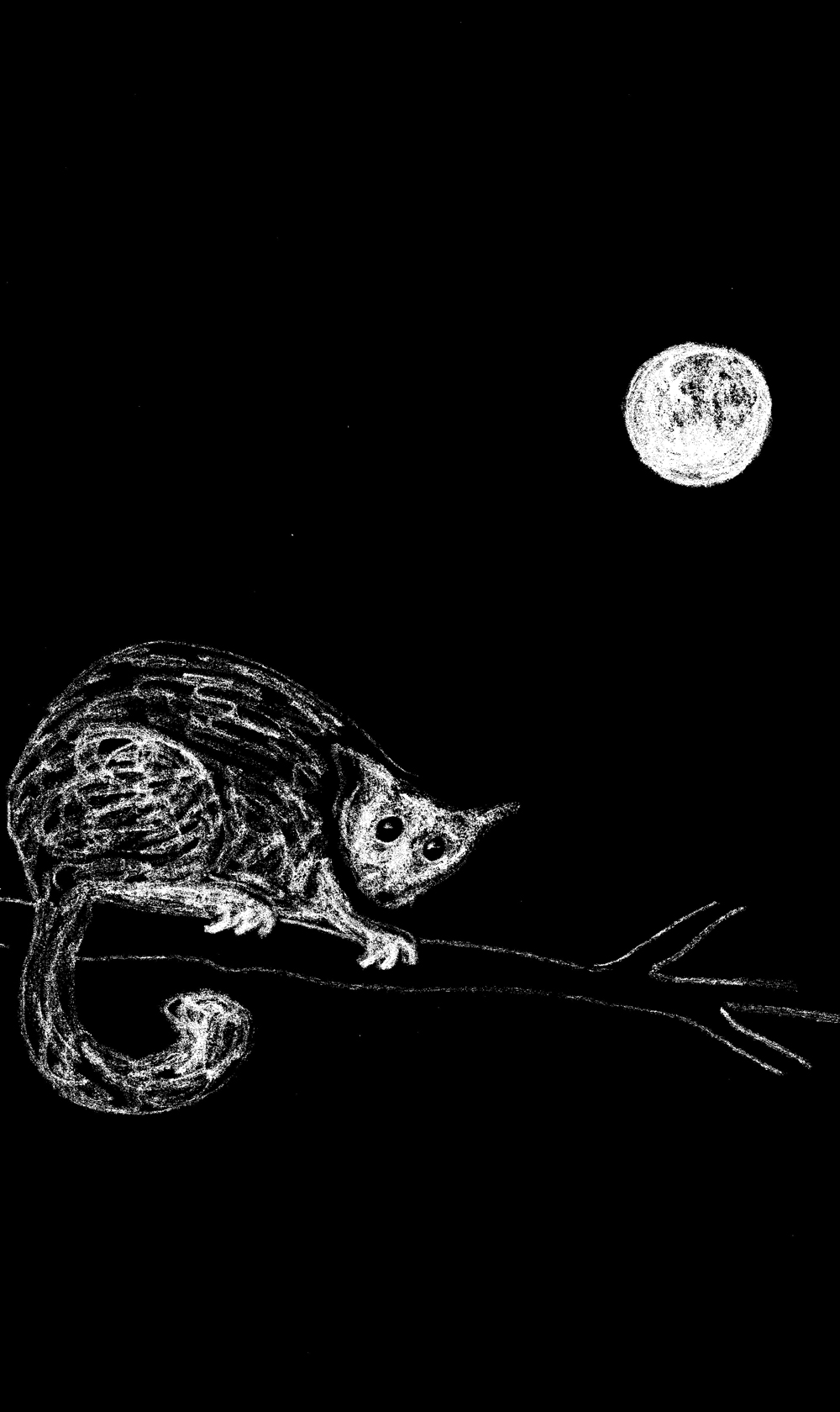

IMAGES: LEONIE BRIALEY

The third in the Nocturnal Series is an essay by Ellen Murphy called “The Dark of Night”, a piece which, due to its nuance and honesty, has had the slightly oxymoronic effect of tightening the focus on some very muddy and uncertain areas of my thinking. Read more

My favourite way to see a place is to walk. As my breath falls into rhythm with the pace of my steps, my mind slows, patterns emerge in the landscape around me and thoughts seem to slide smoothly into place. While in Alice Springs a few years ago, on a hot late-summer weekend, I walked a section of the Larapinta Trail. I didn’t know many people in the town and those I did were busy, so I picked a relatively easy two-day stretch and decided I’d do the walk alone, expecting I’d be sharing the trail with other walkers.

The Larapinta Trail weaves its way for 200 kilometres or so through Arrernte land, travelling west from Alice Springs along the contours of the West MacDonnell Ranges. It sits within an area known as Tyurretye, a place of many culturally significant and sacred sites to the Western and Central Arrernte people. The land was returned to traditional owners on 18 July 2012 and immediately leased back to the Northern Territory Government to be jointly managed as a national park. From an outsider’s perspective, the topography of the ranges is captivating. In the middle of the red, dry desert, rocky slopes cradle perfect oases of water and pockets of lush green vegetation that attract flocks of birds and other wildlife. High atop the ranges you can see for hundreds of kilometres until the soft, purple-red land slowly smudges and dissolves into the sky at the horizon.

In February, the land is hot and arid, baked by the long summer, and as I drove out of Alice Springs, the day was already heating up. The Land Rover that I’d borrowed bounced and shuddered over potholes and the road shimmered and danced ahead of me. After an hour’s drive, I pulled into the car park at Ellery Creek Big Hole. I could hear kids squealing and laughing and then an almighty splash as one of them bombed – knees tucked tight into her chest, eyes squeezed shut – into the cool, deep water and surfaced again with a shriek. Clusters of people were set up around the water’s edge with umbrellas and picnics and great blow-up li-los that floated out onto the water. I laced my boots, reached in for my pack and locked the car. Then, turning my back on the day-trippers and picnickers, I headed towards the trail.

*

At 24 years of age I’d just finished my law degree in Melbourne and, desperate to do something practical after so many years of study, I got on a plane to Alice Springs to intern with the Central Land Council (CLC). I hoped that the skills I’d learned might be of some use and that in turn I would get to learn about how the law played out away from the big cities of the east coast. The CLC is an Aboriginal representative body that assists traditional owners to manage land they’ve reclaimed under land rights legislation or native title. It covers the southern part of the Northern Territory, around 52 per cent of which is now Aboriginal freehold land.

At the CLC I was learning about how the deep sense of identity that Indigenous people draw from their connection to and responsibility for their land has been translated into the language of Western law to substantiate land rights and native title claims. At the time I was there, in 2012, it was nearly 5 years since the Federal Government had compulsorily acquired leases over Aboriginal-owned land as part of the Northern Territory Intervention, and the CLC was working towards formalising tenure on Aboriginal-owned land so that any external body would have to negotiate a lease or licence with the traditional owners.

So when I started my walk along the Larapinta Trail, I had land – and its political power – on my mind.

*

As I began to walk away from Ellery Creek, I was amazed by how much vegetation there was. My south-eastern city mind had half expected an empty desert but the trail wound through dense, spiky grasses and elegantly slender eucalypts. Shielding my eyes from the glaring sun, I walked quickly, absorbed in the landscape. Five minutes in I realised with a jolt that I’d lost the path. I retraced my steps and picked it up again but it made me pause; I’d been blundering forward without much conscious thought. I walked on, slower this time, following the trail as it climbed steadily up the ridge of the ranges, then dropped steeply to trace a narrow valley. Heat radiated off the ground and crumbly red rock skidded drily under my boots. The air fanned at my skin, warm and heavy like breath.

The sun peaked before long and as it began to lower it seemed to beat down upon me more and more fiercely. I walked on and the hours passed quickly. I paused often to drink water but it felt hotter still when I stopped moving. In the late afternoon, as the sun finally began to lose its intensity, I arrived at the Serpentine Gorge campsite. The gorge itself was a little further on and I headed straight there, eager to catch the last of the light. I passed a couple of tourists heading back towards the car park, grey-haired and matching in purple Kathmandu shirts. I expected I’d see them at the campground later.

The trail narrowed through thick scrub. I rounded a corner and the vegetation suddenly gave way to reveal the steep gorge, its red-rock walls mirrored in the pool of gently flickering water. I stood at the edge of the water as the day faded and took in its quiet beauty. It was at once peaceful and full of life; birds and animals called out in the quickening dusk. The rock was all dusty reds and greys. Silver eucalypts jutted from the water or sprouted from patches of earth around the edge.

Something rustled behind me and I turned sharply, startled at how dark it had suddenly become, to find in front of me a dingo picking its way carefully through the scrub. It showed no interest in me, just made its way to the water and drank, but its smooth self-assuredness made me feel awkward and ungainly, like a trespasser. I edged slowly back away from the gorge, careful not to draw attention to myself, not even sure if I needed to be worried.

I picked my way back to the campsite in the half-light and was confused to find it completely empty. There were no other campers. Without people, it seemed eerie, barely a campsite at all, just some vaguely cleared patches of earth. I thought of the dingo standing by the water in the falling dark, blamed it for the rattled feeling that was coming on. I walked on a little further to the car park. Still no-one. The couple that I’d passed earlier must have driven in on a day trip. It was increasingly apparent to me that it was the wrong time of year, far too hot for the tourists I’d blithely imagined would be littering the trail.

I sat down and breathed, then clutched at the familiar process of making camp. Now that the sun had gone down, I felt the need to put some sort of barrier between myself and the environment around me, an instinct that took me by surprise. But, prepared for just one night’s camp, all I’d brought with me was a half-length sleeping mat and a light, plastic bivvy bag, which looked like the body bags you see the corpses being zipped into at the beginning of bad American cop dramas. Without the protection, however superficial, of the thin fly of a tent, I felt unsure of myself, uneasy. The bush around me, which in the light had looked innocent and harmless, was now filled with uncertain shadows, looming shapes, strange noises. This is ridiculous, I admonished myself. What am I? Scared of the dark?

I ate the sandwich I’d packed, then lay back and looked up into the gently shifting trees. I could pick out stars through the gaps of the branches. The dark deepened still and the night grew unexpectedly noisy. The darkness seemed to be amplifying the noises around me, making it difficult for me to tell how far or close their sources were. There were all these creatures alive out there and I had nothing to do with it. Did they know I was there? Did anyone? As I lay there, I could almost feel myself fading away.

I couldn’t remember a time I had felt so vulnerable and I realised I had never been so completely exposed to the environment in this way. I felt acutely how foreign I was to this land and how little I understood it. But I wondered, was it any different at home in the city, inside four walls? Perhaps the structures of the city distracted me from my ignorance, because really, I had little more intimate knowledge about the land there than here.

I thought about what I had been taught at university about the meaning of land in property law in this country. We learnt about ownership, exclusive possession, the ability to alienate, to sell and buy, and it was clear to me then that it was a system inseparable from our culture of consumption. Even the experience I’d had earlier that day, walking through the landscape, now appeared to me essentially consumerist: me on top of the environment, me moving through it, me as a human taking enjoyment from what the environment gave me. I felt in that moment how little those laws of ownership relate to real knowledge of the land that they concern. More than that, I felt how ill equipped I was in my own knowledge system to interpret the noises and shapes as they emerged and receded in the night.

When I first read Mabo,1 the case that recognised native title, I remember being struck by how tenuous our system of property law appeared. In that case, the High Court conceded that the underlying premise for our adoption of property laws from England was false – Australia was never terra nullius and complex systems of land ownership existed in Indigenous societies – but concluded that there was now too much built upon that false premise to undo it. It seemed to me so faith-based, as though we required a stubborn belief in the power of property in order to hold up all the structures of society that are based upon it.

Regardless of the fictional basis of Western property laws, in our society, property and land ownership confer real power, choice and freedom, and I wasn’t so naive as to dismiss the significance of this. At the CLC I’d been learning about the negotiation of mining leases on Aboriginal-owned land. I’d been fascinated by the difference in the property rights conferred by land rights legislation in the Northern Territory as compared to other jurisdictions. Successful claimants under land rights legislation in the Territory received freehold grants, meaning traditional owners have actual rights of veto over what happens on their land. Aside from the cultural importance of allowing traditional owners to have custody over the land for which they have such intimate knowledge and responsibility, it created a source of income, a powerful negotiating position and the potential for self-determination.

*

There in the dark, out of my depth, a lone tourist, I could not avoid how ignorant I was about the place that I was in. There was something in the quality of darkness and night and my total aloneness that stripped away all that I thought I knew. That night I slept fitfully, always hyper-alert, but just before dawn I slipped into a short, deep sleep. When the morning came, the air was pleasantly fresh. I shivered, enjoying the chill, knowing that within a couple of hours it would again be brain-sappingly hot. I sipped some water and looked around, trying to reconcile the gently rustling trees and soft calls of birds with the strange noises and shapes of the night.

I packed up my things and started walking, feeling very small and very quiet in that great desert.

1. Mabo and Others v Queensland (No.2) (1992) 175 CLR 1

The Nocturnal Series is entirely funded by donations from our readers. Please consider clicking here and supporting Chart Collective with a donation. Chart Collective is a not-for-profit publishing project that believes creators should be paid for their work. Without advertising or corporate partnerships, paying authors and artists means we rely on contributions from our readers. In the interest of transparency, we welcome inquiries about Chart Collective finances.